An Gerlyver Meur - The new Cornish dictionary

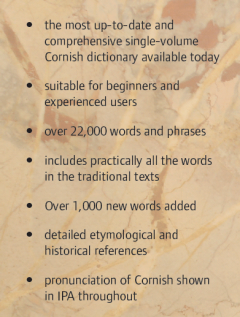

To anyone interested in the Celtic languages, in particular the Brythonic branch, the publication of a new up-dated edition of An Gerlyver Meur, Kernewek - Sowsnek, Sowsnek - Kernewek, is an event to savour and celebrate.

It is claimed that inside every Welsh person a poet is bursting to get out. Inside every Breton, it is similarly said, there is a grammarian struggling to get out. I suspect the same is true for the people of Cornwall, practical people, inventors, hard-working, the stuff of which compilers of dictionaries – such as this one - are made.

There is a heavy-duty beauty about dictionaries. They are not books to be read once and cast aside. They are the tools and providers of vital raw materials, the work of diligent, meticulous men and women for the benefit of us hack-writing mortals.

Since the publication of the first edition in 1993 there has been significant development in studies of the Cornish language, notably because of the discovery of old manuscripts. The most important was the mediaeval play Bywnans Ke (The Life of Kay) discovered among the papers in the office of the late Professor J. E. Caerwyn Williams in Aberystwyth in 1999.

A detailed study of this manuscript alone made a considerable addition to the body of Cornish literature in the Middle Ages. It also contributes 250 previously unknown words to the Cornish lexicon – many relevant to our day and age, such as kedhlow (information). Thanks to additions from other similar sources, proverbs and sayings, An Gerlyver Meur is three times the length of the first edition.

A language that ceased to be spoken over a wide area of Cornwall as early as the beginning of the nineteenth century to be resurrected in the twentieth century needs the inspiration of word creators – something not unfamiliar to any language and particularly to the Breton and Welsh languages. An interesting innovation of this dictionary is that the conceiver of a new word is given credit in the entry.

I enjoyed seeing words like hweger (mother-in-law, old Welsh chwegr) and hwegron (father-in-law, old Welsh chwegrwn). And gourel (manly) which was how I recall the Welsh word gwrol being used in my childhood not as, more commonly, the word for brave. The similarity to Breton is duly noted. Then there is Maria Wynn for the Virgin Mary.

As can be expected, there is an extensive vocabulary of words to do with the sea and marine life. Where there are similar words in Breton or Welsh, that fact is noted. A most useful section for one like myself who is not as well versed as I should be in the vocabulary of nature.

It is a volume to browse with enjoyment, useful as a source of information regarding word similarities in the other Brythonic languages – as well, of course, as the use we normally make of dictionaries.

Great praise goes to Dr Ken George for his work in compiling and editing the work, the work of a lifetime. Here is a true polymath, a scientist who has devoted all his spare energy and devotion to the study of Cornish. A poet, too, who has pioneered the art of writing Cornish poetry using the Welsh cynghanedd as Maodez Glanndour did in Breton.

It was K. George who prepared the first edition of Bywnans Ke for publication by Kesva an Taves Kernewek (Cornish Language Board) in 2006. A voluntary organisation, incidentally, bearing no relation to the Welsh Language Board.

Due praise also to Kesva an Taves Kernewek for publishing this handsome and substantial volume, bound to withstand the wear and tear of time associated with dictionaries.

Gwyn Griffiths

An Gerlyver Meur costs £29.99.

Copies are available from:

Tor Mark Press, United Downs Industrial Estate,

St Day, Redruth, Cornwall TR16 5HY.

Website: (voir le site)

E-mail: office@tormark.co.uk

(voir le site) of BBC Cymru with about the same article, by Gwyn Griffiths, in Welsh : Geiriadur Cernyweg - argraffiad newydd o “An Gerlyveur Meur”

.

■